Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders – Revisiting America’s Unsolved Pharma Horror

In 1982, a wave of panic swept across the Chicago area and soon the entire United States. Seven innocent people died after ingesting Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide—a crime that shocked the nation, reshaped drug safety laws, and has remained unsolved for over four decades.

Now, Netflix’s new three-part true crime docuseries, Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders, returns to the infamous case with gripping interviews, high production value, and the final footage of the prime suspect, James Lewis, who died in July 2023.

A Legacy of Fear and Sealed Bottles

The series opens with haunting visuals and archival media, including a 1981 Tylenol ad claiming, “For relief you can trust, trust Tylenol. Hospitals do.” But trust shattered in 1982 when consumers unknowingly bought Tylenol laced with deadly poison straight off pharmacy shelves.

The aftermath was unprecedented:

-

Seven deaths in the Chicago area, including members of the same family.

-

A citywide ban on Tylenol enforced by police cars and live TV broadcasts.

-

A complete overhaul of tamper-evident packaging across the pharmaceutical and consumer goods industries.

James Lewis: The Man Behind the Letter

Central to the documentary is James Lewis, the man who sent a Zodiac-style extortion letter to Johnson & Johnson, claiming responsibility and demanding $1 million to “stop the killings.” Although Lewis served 12 years in prison for the letter, he was never formally charged with the murders.

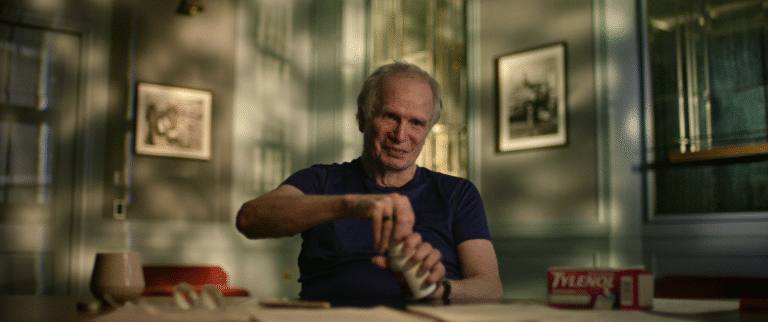

In a disturbing scene from the second episode, Lewis handles a Tylenol box, joking about getting his fingerprints on it:

“Everyone opens a bottle and swears my name.”

The footage, which represents his last known interview, offers a chilling glimpse into the mind of a man many still consider the main suspect—even as law enforcement remains divided.

Dramatic Twists Fit for Fiction

What makes the Tylenol murders uniquely haunting is not just the randomness of the poisonings, but the domino effect of tragedy and misdirection that followed:

-

Stanley and Teresa Janus died after taking Tylenol while mourning the death of Stanley’s brother—who had also fallen victim to the same poisoned pills.

-

A man named Roger Arnold, wrongly suspected, later killed an innocent man resembling someone he blamed for his arrest.

-

Another Tylenol-related cyanide death occurred in New York in 1986, while Lewis was still in prison.

The series also touches on media figures like reporter Brad Edwards and survivor-advocate Isabel Janus, who pursued truth for decades. Yet no definitive evidence has emerged.

How Does Netflix’s Version Compare?

This is not the first time the case has resurfaced in popular media:

-

Painkiller: The Tylenol Murders (2023) – a Paramount+ miniseries (rated 3 stars by critics)

-

Unsealed: The Tylenol Murders (2022) – a podcast by Chicago Tribune journalists Christy Gutowski and Stacy St. Clair

See More ...

What sets the Netflix docuseries apart is:

-

Exclusive final interview with James Lewis

-

High-quality graphics, reconstructions, and archival footage

-

Balanced narrative with conflicting opinions from investigators

Still, the series stops short of delivering new evidence or revelations—highlighting just how elusive closure remains in this case.

A Missed Opportunity for a Dramatic Adaptation?

Despite the drama, tragedy, and cinematic potential, Hollywood has never given the Tylenol murders a full-scale fictional treatment, unlike stories like:

-

Zodiac

-

Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story

-

Mindhunter

-

Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile

With its blend of horror, mystery, and public health fallout, this is a story ripe for a compelling narrative series or film adaptation.

Conclusion: More Questions Than Answers

Even after four decades, Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders reminds us that some of the most terrifying crimes come not from masked intruders, but from anonymous hands tampering with the mundane.

As retired FBI agent Grey Steed notes in the final episode:

“I believe James Lewis not only wrote the letter but planted the cyanide.”

Former Chicago Police Supt. Richard Brzeczek counters:

“James Lewis is an a*****, but he is not the Tylenol killer.”*

Whether justice is ever served remains doubtful. But the lasting impact on drug safety, law enforcement, and consumer trust ensures this case remains etched in American history—and in the minds of anyone who has ever opened a bottle of pills and paused, just for a second.